Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

Fashion headlines in 2025 currently circle the hot-button issue of “fashion musical chairs” with creative director exits and younger designers acesnding at the helm of legendary luxury Maisons. As the fashion industry walks the fine line between managing creativity, consumer trends and profit margins, LUXUO looks back at the designers who once disrupted the system entirely. The visionaries who walked away from the spotlight on their own terms before design ambitions were at odds with TikTok virality and the next celebrity-fronted drop.

While the fashion industry in 2025 is moving faster than ever, some of fashion’s most influential figures have chosen alternative paths. Their stories are not about comeback collections or Instagram dominance but about cultural longevity. While the industry examines who is in and who is out at major houses, these legends quietly continue to build legacies elsewhere — be it through curation, collaboration, education or art. LUXUO revisits the living visionaries of both ready-to-wear and the avant-garde — from Christian Lacroix to Martin Margiela — to trace their continued influence across contemporary design, academia and creative stewardship.

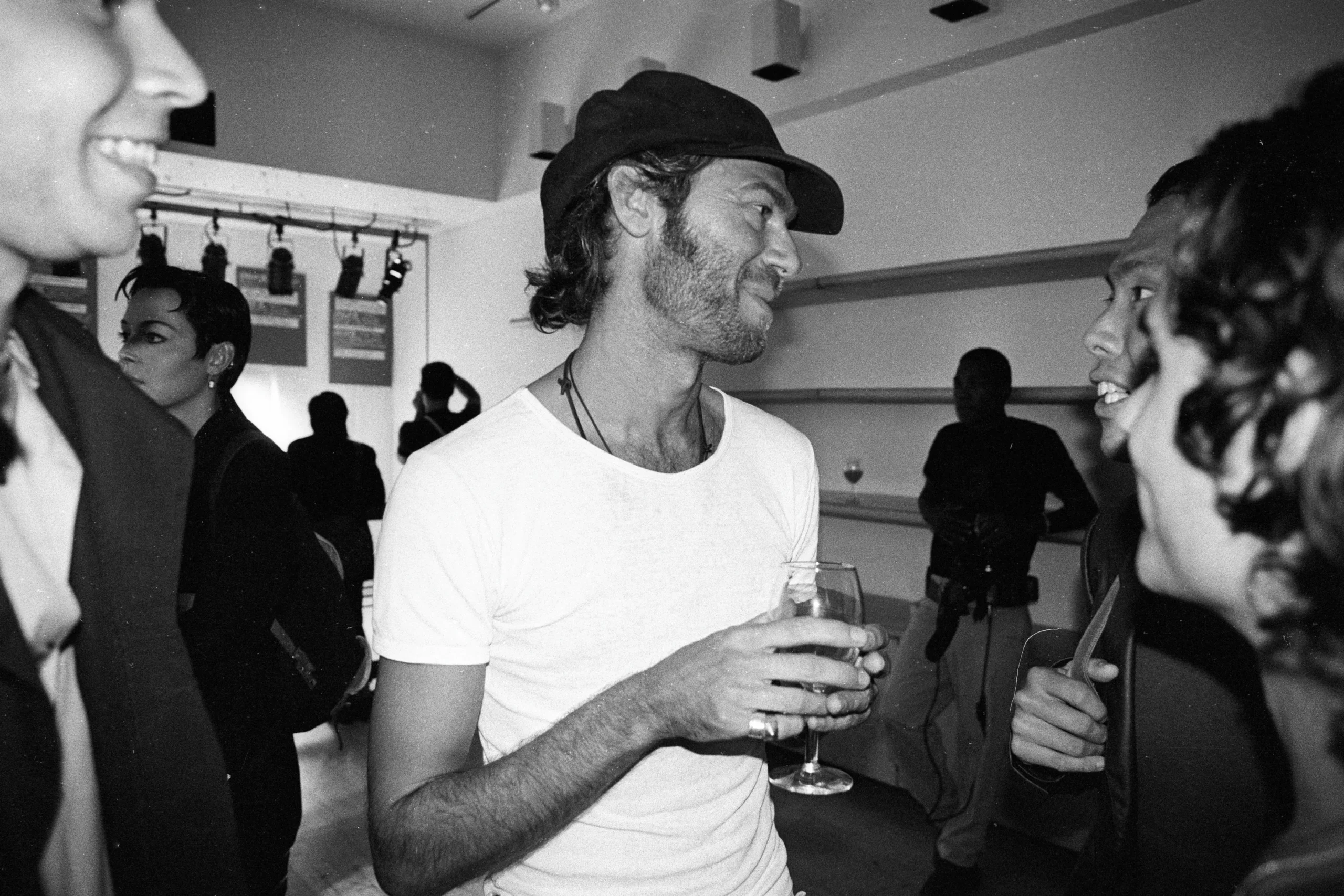

Martin Margiela

Long before quiet luxury toyed with anonymity and anti-branding, Martin Margiela built an entire philosophy around disappearing from the spotlight. Martin Margiela approached fashion as a form of intellectual and cultural inquiry. His designs questioned structure, function and meaning. He used clothing as a medium to critique the system from within, creating a radical stance that redirected focus entirely to the work, not the designer. Margiela’s signature included raw seams, exposed linings and inside-out constructions, which he showcased at abandoned buildings, playgrounds or parking lots — bringing attention to overlooked urban spaces. For many, Martin Margiela is seen as someone who laid the foundation for designers like Raf Simons, Rick Owens and Vetements who came after him.

Since stepping away from his namesake label in 2008, the elusive Belgian designer has fully transitioned into the world of contemporary art. “For me, fashion in its current form has completely lost its appeal. It is now 15 years since I left my fashion house and I have never regretted the decision,” he told Dr. Jeni Fulton, for Art Basel in 2023. Margiela’s current work continues his fascination with deconstruction and the overlooked — themes that defined his fashion practice. Now working across sculpture and assemblage, he engages with found objects, fragments, silicone and materials that emphasise tactility and imperfection. A standout example: “Vanitas,” a piece composed of silicone skin spheres with embedded hairs in varying shades, reflecting aging and bodily change.

Influenced heavily by Surrealism and its presence in Belgian visual culture, Margiela’s pieces often incorporate hair, dust and discarded elements — turning the mundane into the poetic. Exhibited with Zeno X Gallery (Antwerp) and most recently shown at Art Basel Hong Kong (March 22–25, 2023), his sculptures resist completion and challenge conventional ideas of beauty, authorship and the artist’s role. His first solo exhibition was at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, where he presented over 40 artworks. Despite his fame, Margiela has always been known for his anonymity and aversion to the public eye. He still mostly avoids interviews and photos. He was a curator for the 25th-anniversary issue of A Magazine Curated By, marking a rare return to the fashion sphere.

Ann Demeulemeester

Ann Demeulemeester rose to prominence in the mid-1980s as part of a collective of Royal Academy of Fine Arts graduates dubbed the “Antwerp Six”. She launched her namesake label with her husband, photographer Patrick Robyn in 1985 and staged her first Paris runway show in 1991. After adding menswear in 1996, she became one of the earliest designers to present men’s and women’s collections together. Her label’s Spring/Summer 1997 collection was widely praised as the most distilled embodiment of the brand’s ethos. Known for her dark, poetic tailoring and a loyal global following, Demeulemeester stepped away from the brand in 2013, writing that it was mature enough to grow without her. The company — managed via bvba 32 in Antwerp and led long-term by managing director Anne Chapelle — continues to operate standalone stores in Antwerp, Tokyo and Hong Kong.

Ann Demeulemeester has shifted her focus from fashion to interior design. Since 2019, Ann Demeulemeester has collaborated with Belgian design house Serax on an evolving universe of homeware — beginning with porcelain collections (Dé and Ra), cutlery and glassware and later expanding into sculptural lighting and luminous objects. In 2022, the partnership culminated in a full-scale furniture line comprising stools, chairs, tables, consoles and sofas crafted in a variety of expressive materials. Demeulemeester’s approach to design remains as intellectually rigorous as it is emotionally resonant — eschewing fleeting trends in favour of a world that is both deeply personal and contextually relevant. Her work continues to embody dualities: the tension between strength and delicacy, structure and ease, the poetic and the radical, the precious and the utilitarian.

In 2023, Ann Demeulemeester debuted her fragrance, “A” which she described as a deeply personal creation — a distillation of her sensibility and instinct, honed over a lifetime of intuitive exploration. Centred around her initial, “A” was brought to life through a deeply personal lens, with photography and design contributions from her husband and son. Every note of the genderless perfume was composed by the designer herself, drawing on her affinity for nature’s rawest, most elemental forms. Crafted using cold-pressed essential oils of the highest purity, the result is a poetic and enigmatic scent that mirrors the tension and balance so often found in her work — structure and serenity, mystery and clarity.

While she no longer helms the creative direction of her namesake label — now under the stewardship of Claudio Antonioli — she continues to shape its future by consulting on special projects and legacy initiatives.

Helmut Lang

Helmut Lang was once described as the original minimalist disruptor who brought uniforms and industrialism into fashion’s mainstream — and then famously quit at the peak to become an artist. With a design language rooted in minimalism, architectural clarity and an intuitive grasp of subversion, Helmut Lang played a part in shaping the fashion landscape throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. From sharp tailoring to stripped-back branding, his influence persists in the DNA of countless fashion houses today.

Lang’s approach to authorship was equally as radical as his aesthetic choices. Even after donating much of his archive to 20 global museums, his presence remains quiet yet omnipresent despite dodging the spotlight and declining the kind of cult-of-personality that defined many of his contemporaries. Preserved at the MAK in Vienna, his work has outlived its era and continues to speak in the visual grammar of today.

In 2005, Lang stepped away from the fashion industry to dedicate himself to art. The shift was a return to a long-standing calling, as he put it — visual art was his first love. It just took time — and the right rupture — to go back. Based in Long Island, Lang now works with materials that speak of transformation. Discarded rubber, foam, wax and tar — some even remnants of his former life in fashion — are reconfigured into visceral sculptures. They are abstract, yet dense with memory and imbued with the quiet violence of lived experience. In his own words, he is drawn to things with “scars and memories of a former purpose.” Much like his work in fashion, Lang was never formally trained in art. He works by intuition — letting accidents, trauma and history steer the process. Even the fire that destroyed part of his personal fashion archive became material for sculpture — destruction becoming reinvention. “Expensive compost,” he calls it.

Today, Helmut Lang works as a full-time artist, splitting his life between New York and the Hamptons. Lang’s artistic endeavors have been exhibited in various galleries and institutions, including the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles, The Fireplace Project in Long Island and Sperone Westwater in New York. He has also been the subject of solo exhibitions, such as “What remains behind” at the MAK Center — showcasing his sculptural works. His sculptures evoke the human body without depicting it — fractured, raw and in states of becoming. Lang remains deliberately elusive — camera-shy, media-averse, uninterested in celebrity culture. When he is not in his studio and home, he is tending to his garden — where he reflects on climate change and civil collapse. For Lang, making art is not therapeutic as much as it is an obligation and a way to wrestle with the uncertainty of the world and to give it new material shape.

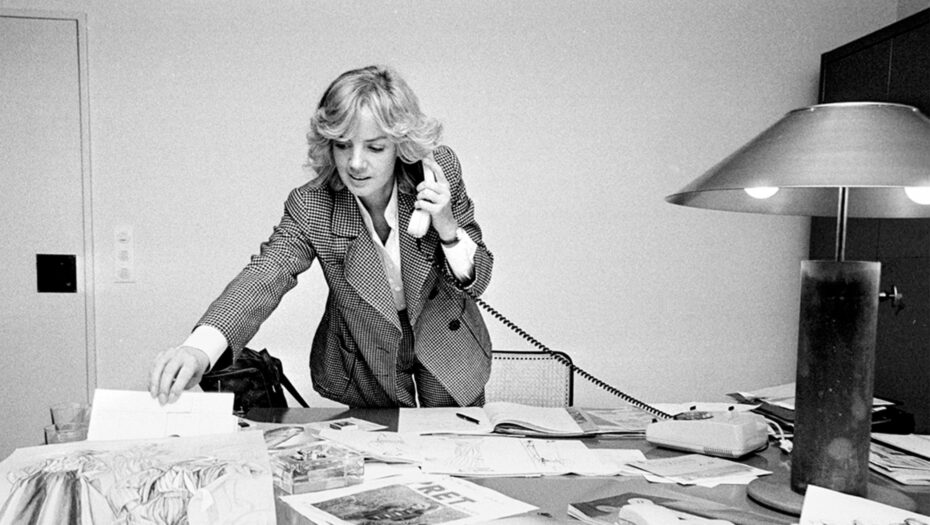

Jil Sander

From the moment Jil Sander launched her Hamburg boutique in 1968 and later her first womenswear collection in 1973, Sander relentlessly refined a sartorial aesthetic rooted in modernity. Her work stood in contrast to the flamboyance of the 1980s, offering instead a quieter, more intellectual sensuality that would become her hallmark. Guided by a desire to redefine women’s fashion, Sander’s garments sought to challenge outdated gender codes. Her fragrance “Pure” — released in 1979 — embodied this philosophy both in name and design. By the 1990s, her influence had permeated the fashion industry. Despite multiple departures from her namesake brand — most notably after its acquisition by Prada in 1999 — Sander returned intermittently, leaving an imprint each time. Beyond her brand, collaborations such as the widely popular +J line for Uniqlo allowed her purist vision to reach a broader audience.

While she has stepped away from fashion as a full-time pursuit, Jil Sander has not retired from design. Instead, she has shifted her creative focus into new industries — most recently, furniture. Her latest venture sees her collaborating with the storied German brand Thonet, reimagining the renowned S 64 chair by Bauhaus designer Marcel Breuer. Sander’s design language is defined by an acute sensitivity to proportion which translates seamlessly to furniture. As she herself says, “Once you build surroundings according to your taste, every new interest will fit in.”

Now based in Hamburg, Sander works between two 19th-century villas that she renovated with the same exacting eye that once shaped her fashion collections. These serene, light-filled spaces are as much part of her creative process as her studio once was. In 2024, she released “Jil Sander by Jil Sander,” a career-spanning monograph created in collaboration with designer Irma Boom and scholar Ingeborg Harms. Unlike traditional retrospectives, the book is immersive and reflects the rhythm and complexity of a fashion show. Filled with layered imagery and personal reflections, it offers rare insight into a designer who has long avoided the spotlight. Despite stepping away from the commercial demands of the fashion industry, Sander’s presence remains as strong and influential as ever.

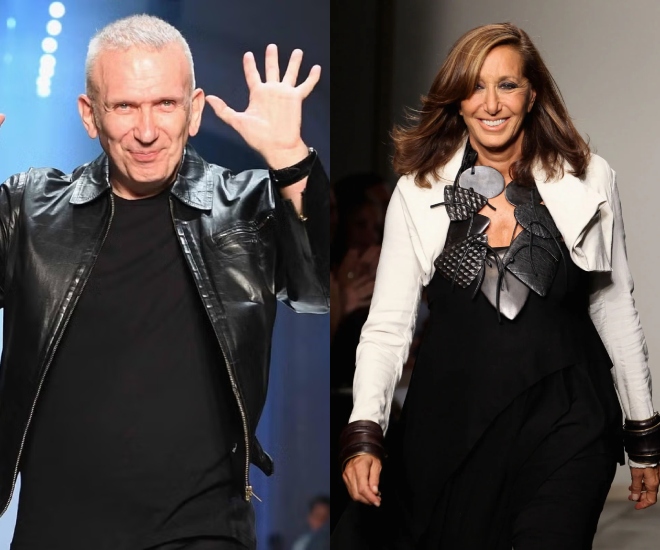

Donna Karan

At the height of her success, Donna Karan was not just designing clothes but a new way of dressing for modern women. When she launched her namesake brand in 1985 after working under Anne Klein, Karan brought a deeply personal vision to American fashion that acknowledged the complexities of modern womanhood. Her breakthrough concept — “Seven Easy Pieces” — was seen as both a capsule wardrobe and a sartorial philosophy. With a few interchangeable staples such as a bodysuit, tailored jacket, skirt, trousers, cashmere knit, leather layer and an evening look, Karan offered women a practical uniform that could shift effortlessly from day to night, boardroom to cocktail hour.

After decades at the forefront of fashion, Donna Karan stepped down from her brand in 2015. Though Donna Karan faced some criticism over her political views, the brand’s decline in the 2010s was largely a result of evolving consumer tastes. The empowered, career-driven woman who defined Karan’s vision in the ’80s and ’90s no longer reflected the priorities of a new generation. She shifted her focus to the creation of “Urban Zen”, a lifestyle brand and philanthropic foundation launched in 2007. Urban Zen is rooted in wellness and conscious consumerism, reflecting Karan’s belief that design should heal and empower. Through the foundation, she tackles issues like burnout in healthcare, trauma in underserved communities and the erosion of culture in post-crisis regions like Haiti.

Now in her mid-70s, Donna Karan remains a force in the wellness and philanthropic spaces. She is active on social media (@donnakaranthewoman), where she shares glimpses of her current passions: horses, healing, family and the evolution of her work through Urban Zen. Though she no longer oversees the Donna Karan New York brand, recent campaigns under the direction of G-III Apparel Group continue to embody the brand’s original spirit, updated for a new era. Karan’s wealth — estimated at USD 590 million in 2025 by Forbes — reflects not just her commercial success but the enduring relevance of her ideas.

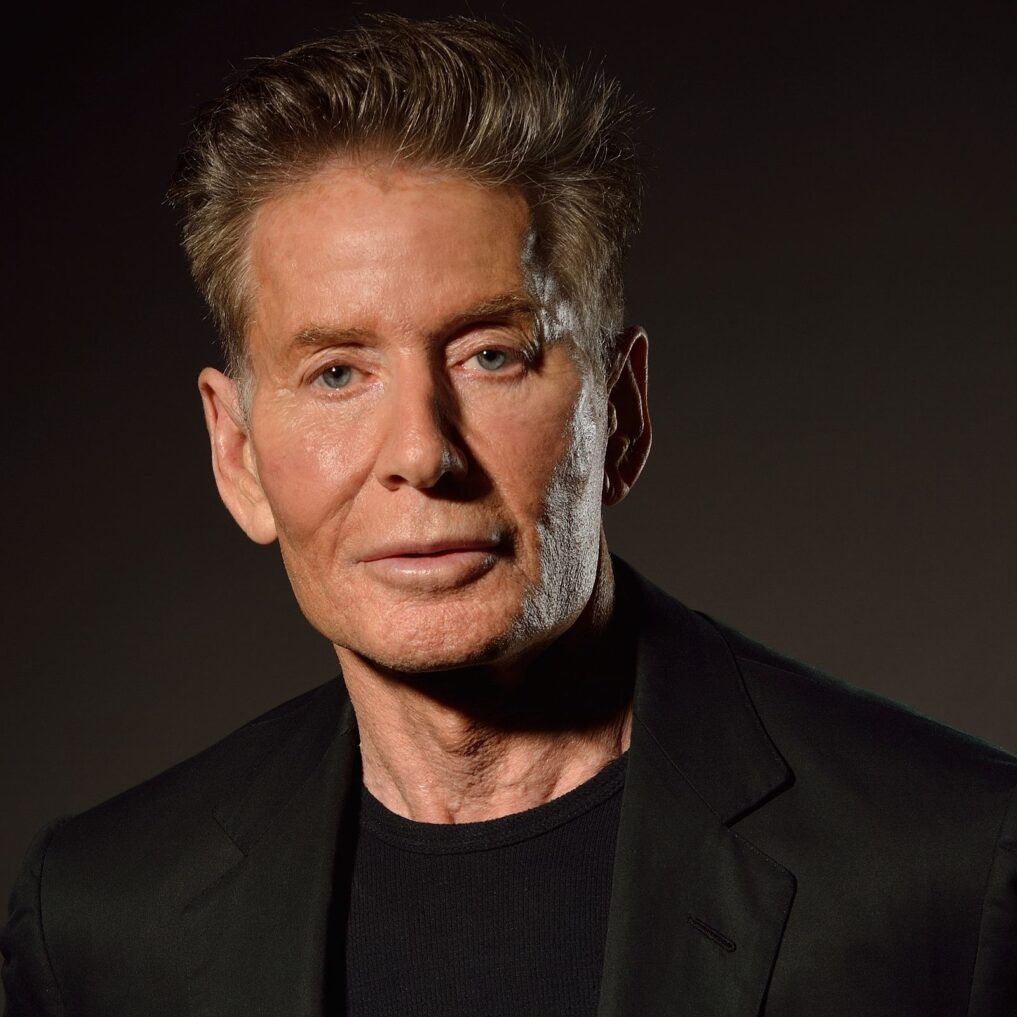

Calvin Klein

Calvin Klein built his empire in 1968 with a line of coats and dresses, becoming a cultural force through minimalist tailoring, provocative marketing and a laser-focused understanding of the American zeitgeist. From revolutionising denim in the late ’70s to turning underwear ads into high art in the ’90s, his brand was about image, sex and confidence as much as it was about the clothes itself. Though he stepped away from the brand over two decades ago after selling it to PVH Corp., Klein’s influence remains deeply woven into the brand’s DNA.

Since the sale, Calvin Klein has not been involved in the design or business decisions of the Calvin Klein brand. Calvin Klein has been known to purchase and sell high-end properties, including homes in the Hamptons, Miami Beach and Los Angeles. Despite no longer being at the helm, Calvin Klein’s name and CK initials remain highly recognisable in the fashion world. Fragrance became another pillar of the brand’s success. Scents like “Obsession”, “Eternity” and “CK One” earned hundreds of millions annually, with “CK One” alone generating over USD 90 million a year at its peak. In 2003, Klein sold his company to PVH Corp. in a deal worth over USD 700 million, including cash, stock and royalties — securing his place among the wealthiest self-made figures in fashion.

Klein has built a personal real estate portfolio — from an East Hampton estate sold for USD 85 million to a minimalist oceanfront compound in Southampton and a modernist mansion in the Hollywood Hills, his homes reflect the same design philosophy that made him famous. Though he has largely stepped out of the spotlight, Klein still makes occasional appearances at industry events and remains active politically, especially in support of Democratic candidates, LGBTQ+ causes, AIDS research and mental health initiatives.

Jean Paul Gaultier

Jean Paul Gaultier forged a five-decade-long career that redefined fashion through rebellion and a refusal to conform to industry norms. Breaking into the fashion industry at just 18 without any formal fashion education, he landed a position with Pierre Cardin after sending his sketches directly to couturiers. By 1976, he had debuted his own collection and by 1983, launched his eponymous fashion house — laying the groundwork for a legacy that would push boundaries like few others. Gaultier’s designs have always stood at the crossroads of art, activism and pop culture. Drawing inspiration from multicultural sources — ranging from Mongolian warriors to Parisian street style — his work was subversive. Throughout the ‘80s and ’90s, he forged powerful creative partnerships with cultural icons. His most famous collaboration — designing the iconic cone bra for Madonna’s Blond Ambition Tour — cemented both of their reputations as provocateurs.

Jean Paul Gaultier is no longer the creative director of his namesake fashion house, having retired from that role in 2020 — selling the company to the Puig group. Following his retirement, the Jean Paul Gaultier house adopted a rotating guest designer model for the couture line. In April 2025, Duran Lantink was named the new creative director, marking a shift from the rotating designer system. While no longer designing the main collections, Gaultier remains involved in mentoring and supporting new talent, as well as overseeing the couture collections. He is involved in various other projects, including the “Fashion Freak Show” — a theatrical production inspired by his life and work and the “Cinémode” exhibition. The Jean Paul Gaultier headquarter is located at 325 Rue Saint Martin in Paris. Gaultier ended his ready-to-wear and couture lines but reimagined his legacy by inviting guest designers — from Glenn Martens to Simone Rocha — to reinterpret his archive each couture season.

Christian Lacroix

Christian Lacroix emerged in the late 20th century as one of fashion’s most distinctive voices. From the streets of Arles, France to the grand stages of Parisian fashion week, Lacroix tapped into drama, colour and historical references — challenging traditional notions of couture. His debut collection featured the now-iconic “pouf skirt,” a dramatic, voluminous silhouette that epitomised his theatrical approach. Throughout the late ’80s and ’90s, Lacroix was a mainstay in haute couture, adored for his unapologetically ornate work. Bright colours, opulent embroidery, corsetry and historical references were hallmarks of his collections.

Despite his fame and critical praise, Lacroix’s brand faced financial instability. The label struggled to turn a profit in the 1990s and in 1995 it was acquired by LVMH. Though Lacroix stayed on as creative director, he had little control over business decisions. By 2009, after years of losses and limited commercial traction, the brand declared bankruptcy. Lacroix — disillusioned with the corporate structure and mourning the loss of his creative independence— exited the fashion house. Post-bankruptcy, Lacroix returned to his roots: the world of costume design. He has since created lavish looks for opera and ballet productions across Europe, including Carmen at the Opéra Royal de Versailles and La fanciulla del West in Hamburg.

He has a long-standing collaboration with the Comédie-Française and has also worked with the Bouffes du Nord, Opéra Garnier, Opéra-Comique and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Additionally, he has a partnership with the Mediterranean brand Desigual. Freed from commercial expectations, he has embraced this stage as one where artistry thrives. While he stepped away from his namesake fashion house in 2009, he has expressed approval of the recent acquisition of the brand by Sociedad Textil Lonia (STL), according to a post on Instagram.

For more on the latest in luxury fashion and style reads, click here.