Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

By Eric Bottjer

One hundred sixty five years ago today, two men in disguise met at dawn at London Bride Train Station. Despite the unseasonably warm morning, each man worea heavy overcoat and top hat. The taller man, the American, wore a fake beard and his coat collar turned up, his face only visible to anyone seeing him head-on. The Brit’s face was clean-shaven and uncovered, and it was he who approached the other with a warm smile and out-stretched hand. The pair spoke for a single minute, remarking on the wonderful weather and the happiness each authentically felt in sharing the upcoming day with the other.

And then the smaller man, Tom Sayers, heavyweight boxing champion of England, boarded one train car with a healthy entourage. His day companion, American champion John C. Heenan, “The Benicia Boy,” ducked into a separate car with a handful of men in tow and the train groaned, its’ cars overloaded, until it gathered enough momentum to take its occupants to history.

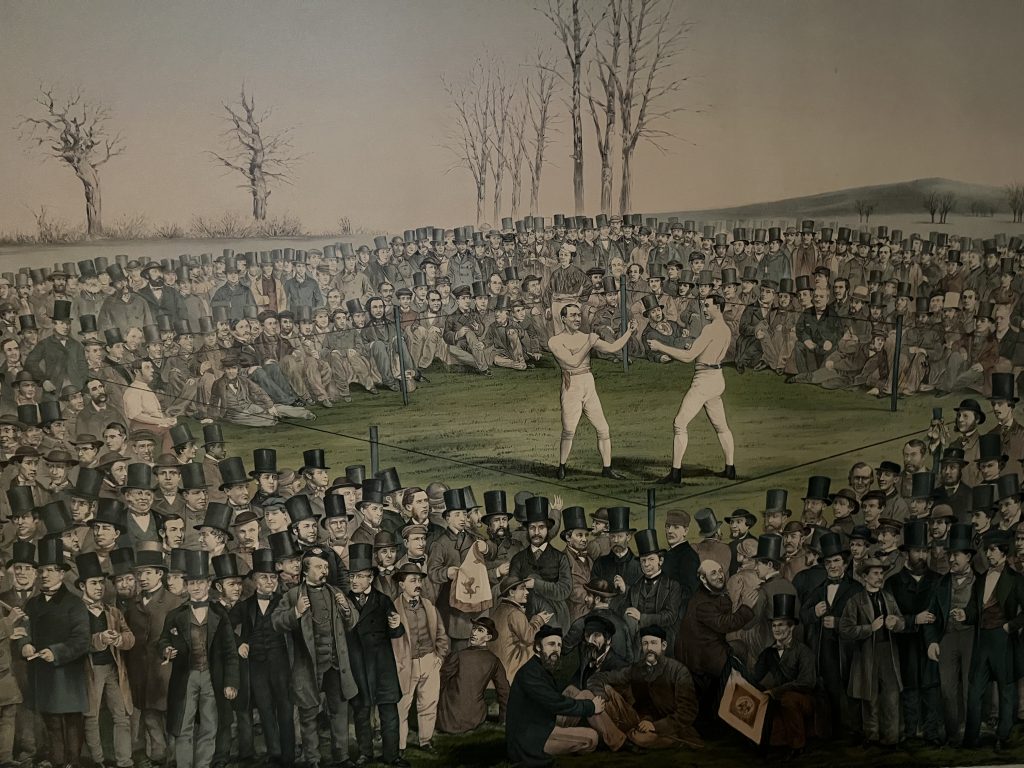

Only the fighters and their confidants knew the destination. When the train stopped some two hours later, it was at Farnborough station, in what would now be a one-hour drive southwest from London. The throng, nearly 12,000 strong, blazed a half-mile through a meadow to where a ring awaited them, assembled a day before. There was no canvas – fights were on “turf” (the ground) and the ring was comprised of wooden stakes hammered into the dirt, with two slack ropes – which were run through man-made holes in each stake – creating a closed space. The ring itself was circled, not by stakes or ropes, but by men. Hard men. Prize-fighters, known violent criminals and former cops, each armed with either a whip or club. This was the DMV between the crowd – already roaring drunk as a whole at 7 am – and the fighters. The referee remained in the DMV.

The Heenan-Sayers match was boxing’s first “super-fight,” and only the second time an American had the audacity to challenge England’s 141-year stranglehold on the world’s heavyweight championship. Only it wasn’t boxing then – it was prizefighting. Rounds were not three minutes. A round ended when a man was downed. And you got a total of 38 seconds to recover from a knockdown. The men – and it was only men – fought with bare fists. Gloves, or “mufflers” as they were called in their infancy, were a generation away. Fights finished when one man could not stand ready at ring center after the 38-second break. Deaths were infrequent, but not uncommon.

Charles Dickens was there that morning. As was the Prime Minister and the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII, the King of England). Every man present was breaking the law, but only Heenan and Sayers risked jail time. Prize-fighting had always been illegal and these matches clandestine, with boxing followers (“the Fancy”) using word of mouth to discover which of the London pubs were selling train tickets the night before to “destination unknown.” Yet the Heenan-Sayers fight was the most publicized secret in history. One contemporary writer surmised it was the most written about event up to that time in human history, an opinion that generated little debate.

Heenan was 26 years old and stood an even 6-foot and weighed 190 lbs. in fighting trim. He was considered a near giant (the average height of a man in England then was a shade less than 5-foot-6). The American out-weighed the average Brit by 50 pounds.

Sayers was a normal 5-foot-8 and today he would fight at light-middleweight. He was 34 and his features bland. Only when confronted with violence did Sayers reveal his depth. He had been a prize-fighter for 15 years when he tossed a cap into the roped area to announce his arrival for the fight. As a novice seven years prior, Sayers lost a 61-round fight to fellow Brit Nat Langham, who wisely retired rather than give a younger, improving Sayers a rematch. Four years later, Sayers won the championship of England by trouncing the aging champion, William Perry, the “Tipton Slasher,” in 70 minutes. Sayers took grim joy in vanquishing much larger men. When hesquared off with the bigger, younger Heenan, Sayers had lost just once in 15 prize-fights (such bouts were brutal affairs, and a fighter rarely had double-digit fights in a career).

Heenan had never won an official prizefight. He was born in Troy, New York, the son of Irish immigrants and headed to California as a teenager to get rich during the 1849 gold rush. Heenan found no gold, but discovered he could earn decent money challenging the roughest of the miners in bar fights. Unusually large and athletic, stories of Heenan’s fighting talents reached back to his home area of New York. He returned there in 1857 and was matched early the following year with John Morrissey, the American bare-knuckle champion.

Morrisey also was raised in Troy (the men were acquaintances as teenagers, but never spoke). Morrisey was Irish-born and he and Heenan drifted in and out of rival New York gangs, working as enforcers during city elections (Morrissey, while champion, was thrashed in a street fight by gang leader William Poole, aka “Bill The Butcher,” illustrating the short distance at that time from street-fighting skills to prizefighting skills, as well as the authentic menace of The Butcher).

Heenan challenged Morrissey in Canada, about 70 miles north of Buffalo (the fight receiving such advance notice that no place in New York could be found where organizers felt safe in pulling off the illegal match). Each man put up $2,500 cash (about $97,500 today) and fought winner-take-all.

Heenan was a wonder, showing skill and power never seen before in an American prize ring, yet he lost. The “Boy” was not in the best of shape and he had damaged his right hand early after crashing it into a ring post during an assault on the ground-giving champion. The crowd of 2,000 was pro-Morrissey and many of his Dead Rabbit gang members crowded ringside. Heenan was occasionally punched by them if he strayed too close to the ropes and endured constant verbal threats on his life. Morrissey was covered in blood after an early beating, but grimly kept attacking and finally finished his younger challenger after 22 minutes.

Heenan and his financial backers cried for a rematch, but Morrissey had just as much brains as brawn. He never fought again, “married up,” became a U.S. congressman and eventually founded Saratoga Race Track.

Heenan’s talents were confined to the prize ring. News of his wonderful performance carried across the Atlantic (Heenan’s chief trainer was an ex-English prize fighter and a former foe of the champion Sayers) and the hype began. Heenan claimed the vacant American championship and sailed to England.

By then, Sayers was ancient as a prizefighter, but it was all he knew. Born in a Brighton slum, the champion was illiterate and a terrible businessman. Prizefighters traditionally opened pubs (becoming “publicans”) and most flourished, as the men, while criminals, were also celebrities and the only way to see them in the flesh – other than attend their fights and risk arrest – was to venture to their watering holes. Sayers lost money in the pub life.

The prize ring was a refuge for Sayers. He had married 15-year-old Sarah Henderson in 1853 and had two children with her. By 1860, his wife was having an affair with a grifter and black-mailing Sayers to support them both, lest she reveal to the newspapers the embarrassing details of her tryst and Sayers’ impotence to stop it. All of Tom’s life tools were confined to fist-fighting.

A woman also tortured Heenan. The handsome pugilist had a whirlwind courtship with Broadway performer Adah Isaacs Menken, a diminutive mixed-race bohemian who gained notorious fame for wearing a flesh-covered bodysuit during one New York performance, earning the nickname “The Naked Lady.” Nobody had ever seen curves like that outside of their own bedroom (or a brothel). The New York Times snidely said of Menken that she was “unhampered by the shackles of talent,” but Menkens interests varied from stage to travel to poetry and feminism. And men. When Heenan ventured to England for the Sayers fight, he and Menken were still married, but the boxer read with distress of her open affairs with actors and writers. Menken was ahead of her time. When Heenan and Sayers toed “the mark” (a line dug into the dirt), they were not only fighting for the championship of the world. Each wanted to regain his manhood.

Heenan and Sayers were both in the ring at 7:45 am. Afirst-time prizefight observer noted the stark contrast between the drunken mob surrounding the fighters, and the organization and ceremony of the fight itself. Both fighters and their seconds were introduced to the crowd, as was each camp’s “umpire” and a neutral referee.“Colors,” ornate scarves representing each man (country’s flags were common) were tied to the neutral ring posts, with the winner taking the loser’s “colors” as a trophy.Each wore the traditional prizefight garb: black soft leather boots, ankle high, with one-inch spikes on the soles to grip the turf. White tights that extended from their waits to the boots, each man wearing a sash tied around their waist, identical to the sashes they tied to the neutral corner. Both were bare-chested, Sayers brown as a chestnut, showing evidence of hours training outdoors. Heenan, fearing arrest after arriving in England, trained exclusively indoors and his skin was so white that one writer dubbed him “The Magnesia Boy.” When Heenan shed his coat after entering the ring, the crowd noticeably quieted. The American giant was a perfect specimen and more than a few present considered for the first time that their champion might have an issue.

Heenan tossed a penny and Sayers called wrongly, giving the American choice of corner. Sayers spent his morning in-between rounds staring at the sun.

“Time” was called (the 19th century boxing version of a bell) and the men sparred in front of a hushed crowd for well over a minute, neither attempting a blow. At one point, each dropped their hands and laughed. That was the last moment without violence.

Heenan forced the smaller Sayers to the ropes, who responded suddenly with a right that crashed into Heenan’s jaw. Heenan countered with his own right, but Sayers ducked and stepped inside with a short right that bloodied Heenan’s nose. Cries of “first blood for Sayers” (betting was heavy on which combatant would draw “first blood”) were in the air when Heenan snatched Sayers and threw him down effortlessly (throwing a man down was legal). Heenan repeated the trick in the second, but this time followed Sayers down and used his body as a battering ram. Heenan stayed at distance in the third, and when Sayers stepped in, Heenan’s left snaked out and put Sayers on his ass. Sayers tried to stay away in the fourth, but Heenan quickly hunted him down and a hard left again sent Sayers down.

The crowd was a hum of shocked mumurs.

Their champion of champions was not only losing, he was being beaten like a child. After Heenan harshly deposited Sayers in the fifth, the American threw up his arms in victory.

In rounds seven and eight (lasting 13 and 20 minutes respectively), Sayers showed why he was champion. His right arm throbbing from blocking Heenan’s horrible blows, Sayers held his ground and landed two savage lefts to Heenan’s face. The American’s right eye immediately swelled shut. In between rounds, Sayers wandered to Heenan’s corner and crouched down to examine his opponent’s face. Heenan, sitting on the outstretched knee of one of his two seconds (no stools then), gave Sayers a bloody grin.

They fought on, the smaller man half-crippled, the American half-blind. Heenan scored all the knockdowns. At times, they fell together. Heenan out-landed Sayers two to one, but Sayers’ blows horribly disfigured Heenan. His other eye began to swell. He became desperate, knowing that he would eventually go blind. As the rounds passed the mid-20s, Heenan’s punches and throws were savageenough to bring audible gasps from ringsiders. Sayers still toed the mark every round in plenty of time.

By round 30, Sayers could barely stand and his grim features no long masked his obvious agony. But he would not quit. Heenan was basically blind, his facial features disfigured to the point where one ringsider remarked it looked as if Heenan’s face had been stung by a swarm of bees.

After more than two hours of gore, the police arrived and began clubbing their way to ringside. As they closed to riongside, Heenan and Sayers squared up for round 37. The blind American forced Sayers to the ropes. Heenan grabbed Sayers’ neck and forced it on the top rope. He was strangling the Brit. A Sayers supported cut the rope with his pocket knife. The pair may or may not have found five more disorganized rounds until the referee declared a draw. The police made no arrests, allowing the pugilists and their followers unmolested back to their train cars. Sayers was carried. Heenan manically sprinted to his, his unspoken message clear: “I could have fought on.” The timekeeper noted the fight lasted 2 hours 42 minutes.

Like all future super-fights, this one had controversy. Who would have won had the fight continued? Both claimed victory, but each graciously accepted their own championship belt at a ceremony weeks later. Heenan and Sayers chatted and found they genuinely liked one another. They made some coin in a UK tour and when Heenan boarded a ship home, Sayers tearfully waved him off.

The pair had one reunion. Heenan returned to Englandthree years later to challenge the new champion, Brit Tom King. A drunken Sayers worked Heenan’s corner. Heenan lost another violent match, and this time there was no doubt he was robbed. A referee allowed King two minutes to recover one round and it was obvious Heenan could only win if King quit or was killed. When Heenan boarded a ship home again, it was the last time he would see England. Or Sayers. John Heenan retired after the King match – his third – having never won a prizefight.

Tom Sayers, normally the picture of health, went down fast. He quit fighting after the Heenan blooding and drank himself to diabetes and death, passing in November 1865. He was 39.

Heenan was also 39 when he died, of turberculosis on a train car at a Wyoming station. At the end, he knew. “I’m going, Jim,” he told a friend moments before losing consciousness. Heenan handled retirement better than Sayers, but his post-ring life was mixed at best.

Adah Isaacs Menken died penniless and alone in a Paris flat of breast cancer at age 33 in 1868. All her high-falutin lovers were gone. She owned only the clothes in her one-room abode. As Menken’s body was lifted from her bed, one of the authorities noticed something near where her head had laid. He moved a pillow to reveal a photograph of John C. Heenan.